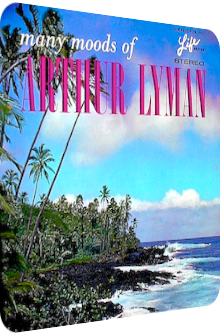

Arthur Lyman

Many Moods

1962

Many Moods Of Arthur Lyman is one of the most self-explanatory album titles in the discography of vibraphonist Arthur Lyman (1930–2002), or so it seems. Many Moods is an overused particle coupling on multiple titles anyway, and there are just about 300 albums out in the wild with this two-word sequence prominently featured on the front artwork. Lyman’s eclectic take of this formula is released in 1962 on Hi-Fi Records and features the talents of pianist Alan Soares, bassist John Kramer and lead percussionist Harold Chang, although all band members are in fluxion and frequently take over parts and additional instruments.

I could end the review right here by telling you that the usual 12 exotic takes are on board and that the band is as successful in their delivery as expected. But Exotica – and first and foremost: life – is not that one-dimensional, so there are both interesting and peculiar tendencies interwoven into the tracklist. A particular topic that was first kicked off in Arthur Lyman’s Percussion Spectacular! aka Yellow Bird (1960) is continued on Many Moods as well where its importance is even augmented: aural trips to Old Europe, and it so happens that the only two songs written by Arthur Lyman himself are about this continent. Without overdramatizing or exaggerating their impetus, they are a continuation of a broader scope, of slowly turning the attention to territories outside the island-centric spheres, planned or not. The other sub-theme is based in Hawaii; two Polynesian songs make it to the album, with the remaining material being placed few and far between, venturing to Asian climes and South American territories. Unfortunately, Arthur Lyman misses the opportunity to present cohesion. Notwithstanding the track title being Many Moods, the mood range is too tiny. But it is still a delightfully exotic album, right? I will give some answers below.

The album kicks off with a Sicilian Holiday, Arthur Lyman is the guide and knows the destination well, for this opener is composed by the bandleader. It can either be considered a delight or an abomination, depending on the Exotica aficionado’s viewpoint; only the melody sounds typically Italian, but it is envisioned with tropical instruments. Lead percussionist Harold Chang is pulling through the Brazilian guiro, its croaking sound conflates with Arthur Lyman’s eight-tone marimba aorta which moves through a thicket of piercing harmonica streams. Once the percussion is revved up with large-grained maracas, rain sticks and Alan Soares piano accents, the aspect of traveling is underlined, the sun-dappled rusticity of Sicily, however, remains. Vibraphone globs round off a strange tune – even by Exotica standards – with lackluster melodies but a great interplay, the latter of which rescues many a genre-related tune, and this is indeed the case here as well.

The next tune is a languorous blast, though: a rendition of Les Baxter’s quasi-macrophotography called Jungle Flower is next, watered by Soares’ piano cascades and Arthur Lyman’s translucent vibes ranging from placid-paradisiac tones to mystical martelato bursts. Chang’s bongo blebs and Lyman’s warbled birdcalls as well as energetic cymbals round off the surprisingly exciting take. It is dreamy and laid-back yet ameliorated by a lot of crescendo phases.

Armando Trovaioli aka Roman Vatro’s Anna is next and continues the Italian theme of Sicilian Holiday. One of Italy’s most famous film composers is exotified, and at least the first few seconds provide a dense, echoey turquoise-tinged percussion shrubbery of distant claves and deep congas, with the famous main melody played on polyphonous marimbas and xylophone accents. Younger listeners might know it from The Avalanches’ Frontier Psychiatrist off the collective’s debut Since I Left You (2000). The transformation of the string-heavy melody to a mallet instrument extravaganza works very well due to the driving percussion layers which are mixed loudly and seem on par with the melody volume level-wise. This leads to the impression that backdrop and foreground coalesce. Not a bad thing in this case, but a welcome expansion of the liveliness.

While Ernesto Lecuona’s dualistic Babalu starts in a melodramatic fashion akin to Lyman’s Bahia off the eponymous album from 1959 and then ventures into a fissured jungle populated by various birds, vibraphone glissandos, dark Honky Tonk piano chords as well as echoey maracas and bongo thickets which accompany the shuttling between the sunny chorus and the archetypical Latin lamento phases, Something Wonderful by Oscar Hammerstein II and Richard Rodgers is a genteel Ambient take with a great intertwinement of Lyman’s quavering vibraphone textures and Soares’ piano alloy. Glitzy ankle spurs and triangles lead to a finale of short-lived staccato-esque kettle drum billows. Unfortunately, Something Wonderful is not dreamy enough to recapture the mellow magic of Hawaiian Sunset (1959) and is almost torn apart by its anticlimaxes. Richard Rodgers’ March Of The Siamese Children finishes side A with a Chinese gong-fueled bustling scenery of Pagan flutes and half-serious, fully fleshed out vibraphone coils, but the melody is too corny and thus destroys the exotic allusions of the textural embroidery. In 1962, Chinese gongs can neither maintain nor guarantee the feeling of escapism anymore. Lyman’s take is too short and jumpy.

Side B opens with something I still perceive as a great idea, regardless of its outlandish dimensions. The Arthur Lyman Group tropifies Miklos Rozsa’s Love Theme From "El Cid," the Spanish Count of Bivar who lived in the 11th century and was later embodied by Charlton Heston in the movie of the same name. What do the historical persona and that Hollywood movie have to do with Exotica? You tell me! Besides, it does not matter, for the grandiloquent melodrama of the lead melody is delightfully modified by the glinting vibe and the dusky piano backings. Enormously sizzling shakers boost the greatness of the theme further. The slow rise of the tension and a sense of adventure are equally tasteful. This is, in the end, an exotic interpretation of a strictly Latin song via the capabilities of a Jazz quartet. John Kamana’s Pua Maiole lets the listener reach Hawaiian shores for the first time on this album, and what a dreamy tune this is! It is basically a beatless duet between Arthur Lyman on the vibes and Alan Soares on the piano, with all the easygoing hyper-dreamy gradients and peripheries Exotica fans love.

Leonard Bernstein’s and Stephen Sondheim’s world-famous America brings back the shakers and drums and sees the melody epitomized by jumpy piano chords and scintillating vibes. John Kramer’s double bass is particularly noteworthy and audible here and shimmers through the euphoric festiveness. Even a birdcall or two ennoble this classic. Let’s be honest: it is a gimmicky take of an eternal evergreen which no one ever demanded, but well-arranged nevertheless. Whereas the band delivers the Hawaii-related conclusion of this album with Charles E. King’s Ka Anoi which is driven by dreaminess and minimalism – soft acoustic guitar breezes and coruscating vibes are all there is –, Arthur Lyman’s own Londonderry Air closes the sub-theme of Europe with this brief visit to Northern Ireland; it is another purified Ambient track, nurtured by the vibraphone, ameliorated by piano sprinkles and rounded off by double bass accents. Oh, and it is exotic! If I did not know the track title, I would not believe it.

I do believe and fear the finale called Planting Rice though. It resurrects Arthur Lyman’s long tradition of ending albums with military marches. Charles Fuqua’s tune is no exception to the rule. Rural piano chords and march rhythms on the maracas make this mallet instrument extravaganza a rather quirky one. You know what to expect when you know at least two or three of Lyman’s albums in their entirety. I simply do not care for march structures in Exotica albums, I’m afraid.

The concept of displaying multitudinous styles and tempos is normally one which should be applauded, regardless of whether this is applied to an Exotica album or any other music-related work. The artist shows his knowledge of various genres, draws from the inspirations of fellow musicians and sure enough makes everyone happy, at least partially so, for if the range is so wide, there must be something in this potpourri for everyone. Curiously enough, this is not the problem of Arthur Lyman’s mood-based incarnation. The opposite is the case, as it features far less moods! As a coherent album, Many Moods Of Arthur Lyman fails. With a bold title like that, I expect 12 totally different mood ranges at least. But the artist only comes up with a bunch of them: a few trips to Europe here, some dreamy Hawaiian material there, in-between them Latin licks as well as American classics.

If you take the title very seriously, Arthur Lyman’s album disappoints. But please, what sane Exotica buff cares for such limitations and lackluster realizations? If one can get over the blandness of both the concept and the title, Many Moods delivers what its title promises – if the listener adores Exotica or Arthur Lyman –, and that is more of the same. The Hawaiian takes Pua Maiole and Ka Anoi are wondrously dreamy, Arthur Lyman’s trips to Europe are standout tracks in that they are written by himself and not based on standards. And then there’s a shiny version of Les Baxter’s Jungle Flower. Contrastive devices would be the quirky take on America and the expected, but increasingly nerve-racking march structures in both March Of The Siamese Children and the closer Planting Rice. Something is amiss in the greater scheme of this album, and that is the cavalcade of colors which the quartet is known for. I do not necessarily demand shedloads of instruments, but if I notice that the Exotica shtick is becoming stale, then things get rather serious. Luckily, this album is only a short – and then by no means stern – misstep in hindsight. Here, the parts are clearly better than their sum.

Exotica Review 282: Arthur Lyman – Many Moods Of Arthur Lyman (1972). Originally published on Nov. 16, 2013 at AmbientExotica.com.