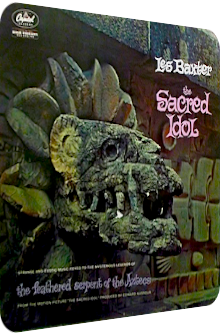

Les Baxter

The Sacred Idol

1960

The Sacred Idol is a particularly cinematic and strikingly orchestral album by Exotica luminary and composer Les Baxter (1922–1996), released in 1960 on his house label Capitol Records. Its cinematic scope is no surprise, for it aurally underlines the B-movie charm of Arnold Belgard's eponymous jungle flick that was later renamed to The Mighty Jungle. The LP works without the film, and it needs to, since Belgard's movie came out a whopping four years after the release of the soundtrack! Spanning the usual amount of 12 tracks, it is a dream come true for those listeners who cannot get enough of mysterious temples, choir-fueled processions, enchanted rain forests and the idolization of artifacts as well as long-lost cultures.

In a curious twist of affairs, Les Baxter is not even the first composer to visit these themes in an Exotica context, as accordionist and soon-to-be film musician Dominic Frontiere covered this mélange a few months prior with his superb Pagan Festival (1959), one of the very best symphonic Exotica suites ever created. This is not to say that The Sacred Idol is a reaction to the short-lived, pre-Indiana Jones or proto-Lara Croft temple craze, let alone Frontiere’s work itself, but whatever trigger caused Baxter to mould these themes into a cohesive work, one should be thankful. And it is true, the album bursts at the seams idea-wise as well as in regard to its grinding, turbulent percussion and drum patterns. Add gleaming horns, mountainous flutes and large choirs to the scenery, and you get those typical Baxterisms… in tripled form. There are soothing passages and even mildly turbulent constructions on board alright, but make no mistake, the signature element is the impetus, the whirlwind of timpani, kettle drums, congas and djembes that reign in the inner-musical realm. Aficionados of classical music will laugh my comment away, but I truly think that The Sacred Idol is the composer’s most eclectic snd complex work ever. As such, it is both intriguing and – in the given context of Exotica – quite demanding.

Les Baxter’s idolization launches with what I would call a pompous opener even by the composer’s standards, for it runs for over five and a half minutes and is undoubtedly his longest vintage Exotica cut ever created. And it is even a real exotic arrangement, not a Space-Age one camouflaged as Exotica: Procession Of The Princes is supercharged with humming mixed choirs, several cymbals and hi-hats as well as delightfully polylayered vibraphone tones which spawn mystique whenever they appear. Throning brass eruptions, xylophone-accentuated flute tones, polyhedric percussion layers and a magnitude that would make this a spectacular outro round off the superb scenery. Choir solos, drum interceptions and a benign climax are totally worth it.

The following The Feathered Serpent Of The Aztecs can only be a letdown, as it sure enough cannot cram that much variety in its physiognomy, but the delicate oscillation between enigmatic shadiness and technicolor euphonies is still magnificently presented. The timpani and Chinese gongs drone portentously, all the while the bongo shrapnel accompanies the acoustic guitar-underlined flute and choir susurrations. From its Ambient stage to its histrionic conclusion, this second tune succeeds mercilessly.

Fruit Of Dreams meanwhile foreshadows Les Baxter’s aqueous journey Jewels Of The Sea (1961) with its prelude of moist harp helixes and glockenspiel globs, and granted, the oceanic gestalt is maintained throughout the runtime and further augmented by Pagan flutes and humming choirs. The enchantment and gravity of said fruit is flawlessly transformed into music, Baxter creates a zoetrope of zealous magic. The follow-up Pool Of Love is particularly compatible with the specific needs of listeners who favor that certain Exotica quartet sound. It is of course still played by the orchestra, but the Martin Denny-esque martelato piano tones, the Harold Chang-evoking guiro that drives the Cha Ca Cha groove as well as the hyper-polished flute-and-vibraphone couples make for an eminently Pop-oriented hymn and a strong corker right from the get-go.

The mystique takes over again in the shape of Aqueducts which kicks off with spiraling flutes, followed by almost bone-crushing timpani stampedes, melodramatic chanters and thunderous cymbals. Quieter phases of tension and opaqueness lead to partially friendlier sections, but make no mistake, this is basically Les Baxter’s black sheep with no embracing ornaments. Akin to Dominic Frontiere’s composition Temple Of Darkness off said Pagan Festival, there is literally no love for sale. The Games finishes side A with a ritualistic and very tribal percussion aorta loaded with rhythm xylophones, grinding boo-bams and staggering timpani. The textural variety is greater than on Aqueducts, and yes, there are short chords of Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov’s Danse Arabe woven into the scenery, but the adamant focus and oomph of the procession make this a highly earth-shattering interim endpoint nonetheless, no matter the vocal solos and besotted harmonies in its second half.

Side B launches with Conquistadores, a cautiously Latinized hymn in the style of orchestral evergreens such as Granada or Poinciana. The horns gleam extraordinarily, the staccato nature of the arrangement implies hectic movements, with only short reflective sections of grace and ambience implying mercy and mutual understanding. Gardens Of The Moon is a much dreamier effort, charged with lovestoned hums, pristine vibraphone glitz and strikingly catchy formations. Only the second half implies gargantuan pompousness instead of solemnity, but this is up for debate. While the stupendous Temple Of Gold focuses on sunset-colored piano tones, Flamenco strings, flute tones in the limelight and critter-like percussion layers which crawl around the temple’s sylvan tendrils, its foil Pyramid Of The Sun worships pentatonic tones in a glistening fashion, weaves liquedous harp drops into the hallowed halls and finishes the aura via multiplexed rays of clinging percussion, with a careful flute tone placenta further illumining the dazzling crypts.

With High Priest Of the Aztecs, Les Baxter gyrates around Orientalism in the form of dun-colored flute tones of portent and a wealth of Native American percussion schemes that remind of Elisabeth Waldo’s carefully researched LP’s such as Rites Of The Pagan (1960). The ligneous marimba droplets scatter tipsily, dark piano tones and croking guiros make are shrouded in twilight, a light which fortunately brightens up over the course of this multifaceted arrangement and reaches its peak on the infamous Acapulco, a gorgeously flamboyant, outright sun-soaked and mightily catchy final anthem which feels horribly wrong in the given context, but the composition itself shines. Celesta melodies and marimba crystals, ever-changing rhythm patterns, an amicable mixed choir and the felt perception of a road trip through bongo-amplified verdured tropics make Acapulco the gorgeous landmark to desire. Yes, it does feel de trop and would be better suited in other albums of the luminay’s oeuvre, but I am not complaining.

If I were a spoilsport and meanspirited (I’m only one of those actually), I would degrade The Sacred Idol as a quick reaction to Dominic Frontiere’s similarly themed opus eximium Pagan Festival, as that record features a comparably colorful wealth of enthralling tone sequences, patterns and humongous walls of brass layers, but such a remark would be wrong, as it is surely Frontiere who is inspired by Baxter’s previous albums, not vice versa. Besides, Baxter's LP is a movie score after all, and yes, it sits on the diametrically opposite spectrum: Baxter's soundtrack is fantastic, Belgard's movie only manages to emit a dubious charm. Be that as it may, The Sacred Idol takes a special place in Les Baxter’s complete works: it is a dedicated and totally devoted embracement of the orchestral Exotica genre in that the drums and percussion strata are even more droning, menacing and gigantic than in his other works. Melodies are strong as usual, but for once the record is much more about atmospheres and movements.

Indeed, it feels as if one moves through temples and copses, takes part in processions and wanders around monolithic architecture. The idolization process is wondrously envisioned: the choir, wideness, density and textural pool work in tandem to create a magical place. If there is one flaw to impose onto The Sacred Idol, it could be its all too dramatic proportions and the quick succession of oases of circumambience followed by a medulla-emptying megalomania. I say “way to go,” but can totally understand if listeners favor Baxter’s smarmier and silkier efforts. If you want fireworks, action and movements that are farther away from the Easy Listening c(o)urse, and if you favor the sub-themes of Paganism, rituals or lost temples, The Sacred Idol is the album to own. Its languorous Ambient pieces such as Fruit Of Dreams and Gardens Of The Moon cater to lovers of dreamier pieces, almost everything else is accessibly labyrinthine and varied. Available on vinyl, CD and a download on Amazon MP3, iTunes and cohorts.

Exotica Review 424: Les Baxter – The Sacred Idol (1960). Originally published on Apr. 4, 2015 at AmbientExotica.com.