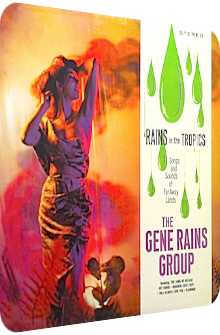

Gene Rains

Rains In The Tropics

1962

2012 marks the 50th anniversary of Gene Rains’ third and ultimate album. Rains In The Tropics is hailed by Exotica fans as the pinnacle, the holy grail, the nonpareil and definite hallmark of his group. Released on Decca Records in 1962, the band comes up with another dozen of renditions that oscillate between dreamy landscapes, lush primeval forests and mystical sequences. And yet a lot has changed as the group has evolved and is at their peak, both creatively and in regard to their instrumental skills.

While their 1960 debut Lotus Land was a journey through resplendent forests with scattered birdcalls and, at least in hindsight, surprisingly eclectic setups and compositions, 1961’s follow-up Far Across The Sea is nicknamed The Dreamy Album by me, for the band mimics the mellow reveries of Arthur Lyman’s releases and establishes a mellifluous aura in most of these tracks. Rains In The Tropics is the band’s most melodious and accessible album, meshes the distinctive styles of both previous works and adds a strong Far Eastern flavor to them. History has it that the band never came up with unique material, but the roster of 36 songs in total always provides a convivial, colorful aural voyage through exotic landscapes.

Their last album is chock-full of melodies and moods, and even though Gene Rains and his band mates – pianist Bryon L. Peterson, bassist Archie Grant Jr. and drummer Allen Watanabe – strive through different, oftentimes contradictory territories, they somehow altogether manage to present the output in a cohesively apollonian way. Without further ado, here’s my in-depth review of Rains In The Tropics, followed by secretly shed tears in the conclusive paragraph.

Bangkok Cock Fight, that’s the first destination and incident of Rains’ last album. Originally written by Les Baxter and featured on one of his slightly darker Exotica albums, Ports Of Pleasure of 1957, Gene Rains needs only one instrument to start this song properly. And sure enough does Watanabe beat the Chinese gong whose sustain makes room for a fascinating ambiguity: for one, Peterson’s piano chords are rumbling along in both a sunset-red tonality and in brighter territories, but it is their coupling with Rains’ droplets on the vibes that add a loftiness to an otherwise rustic track full of clanging cymbals and mellifluous maracas. The middle section features a splendid piano solo by Peterson that morphs yet again from a Honky Tonk flavor to a vivifying mirth in higher regions. Rains’ dreamy vibraphone cascades float to the last, percussion-enhanced repetition of the motif, before Tiki is presented.

There are many tunes called Tiki, Les Baxter did one as well, and it’s always hard for me to group them together and sort them by the writers. This version is unknown to me and remains curiously neglected in the realms of Exotica, and once you come across a title with the same name, it’s surely not this tune. However, it’s a magnificent version with shedloads of mystique and mellowness. A rudimentary four- to six-note piano base frame distantly similar to the Quiet Village classic is meshed with iridescent wind chimes and superb vibraphone sparkles. This time it’s Peterson who elevates this song to memorable regions due to the polyphony of his piano chords that inherits both pompousness and mean-spirited glints. Even though the mood is laid-back and not much seems to happen throughout the duration, it’s the scope of the piano melody that carries the whole song, but the mystery chimes are nonetheless great counterpoints to the majesty of the piano. A towering, masterful piece and one of the best offerings of the Gene Rains Group!

While The Song Of Delilah by Jay Livingston, Victor Young and Ray Evans inherits the dusky mood of the original that is perfectly captured by Latin piano harmonies, rhythmic changes and an unexpected spy theme flavor thanks to Rains’ vibe sprinkles that are dripping through the piano heaviness, Lani Muk Sang’s Mapuana is a tremendously phantasmagoric piece in the best tradition of Arthur Lyman whose mellow mallet instrument washes are equally mesmerizing and without a doubt the role model for Gene Rains’ interpretation. Launching with cymbals and a rising motif on the vibes that create a beautifully blurry haze, this song is the clear counterpart to the piano-driven Tiki and The Song Of Delilah. Here, it is mostly about Rains and Grant Jr., the latter who accentuates this daydream with gentle double bass accompaniments. Soft percussive stabs by Watanabe and Peterson’s short piano bridges round off this hammock-friendly song. The vibes are glinting and melting, the sustain of one note merges with the following, and the reverberating tremolo effect is luxurious and resplendent. Yet another masterpiece on side A that truly showcases the improvement of the band.

Up next is Soshu Night Serenade, written by Gil Baumgart and probably best known for Martin Denny’s interpretation on his album Exotica II where it is prominently featured as the opening track. Gene Rains is able to top Denny’s version with a gorgeous Far Eastern setting due to the omnipresent use of a koto, enigmatic wind chimes and the incessant aural cymbal creeks at the beginning phase. Rains later accompanies the koto with his vibes, and when Peterson joins with his piano, the listener experiences an easygoing song whose three main instruments meet, mesh and depart, playing in typical Far Eastern tone keys. There’s one addition missing in Denny’s version that catapults Rains’ version to the top, and that’s the spiraling four-note motif on the vibraphone that is repeated time and again beyond the middle of the track. It’s almost aquatic and resembles the dancing moonbeams on a coast. Despite its simplicity, it underlines the dreamy setting in the best possible way.

This is the third gigantic track of side A, the latter of which is closed by a majestic rendition of Leo Diamond’s Off Shore. Meandering cymbals, wave-like glitters of the piano and vibraphone notes that submerge and emerge and a double bass-underscored middle section make this a rather heavy rendition that merges between nostalgia, melancholy and dreaminess. This would have been the perfect closing track for the album, as it is no merely ephemeral Exotica ditty, but contains an implied importance and enshrinement that is unusual for the genre and the group.

Side B starts with the tropical percussion of Shadow Of Love, a song co-written by Les Baxter and Lenny Adelson. This percussive backing complete with vivid bongo beats and wood sticks, however, doesn’t serve the song too well, for the mood isn’t exhilarative rather than solemn and distantly doleful. It’s the strangest song of the album, as the ingredients themselves are top-notch. The dynamic percussion solo in the middle of the song is fantastic, and the jauntily falling glockenspiel sweeps add another layer of plasticity to the mix, it’s just that the piano notes are too serious and much too warm for the exuberant counteractions of the percussion sections. Since such undertones and moods are welcome additions to many an Exotica fan who prefers the darker side of the genre, I won't slate the tune per se, as there is really anything wrong with it.

The next song, however, makes me forget about this rare dud: Lonely Winter by Henry Mancini and Rod McKuen is one the menu, and the Gene Rains Group knows how to retain the iciness and put it into a new setting. Bold Far Eastern piano waves, tambourine cameos, high-rise vibraphone crystals and the faintest adumbration of Grant Jr.’s bass make this a fragilely twinkling version. It’s hard to describe this composition in greater detail, as the various melodies fit perfectly together, but retain their distinct quality. It’s a splendid winterly piece with a strong Japanese flavor. Not overly tropical, but well-integrated nonetheless.

While I Will Always Love You by Tony Todaro revisits the balmy mirage of Mapuana and is thus a suitable addendum thanks to its vivaciously glowing vibe sparks, their spacious sustain and the terrific wind chimes percussion that is coupled with plinking sea shell (!), Ted Grouya’s and Ed Anderson’s symphonic masterpiece Flamingo is featured on Rains In The Tropics in a well-adapted version with a hugely exotic factor due to the various keys and characteristic traits of the vibes, an awe-inspiring performance by Peterson on the piano who manages to integrate the yearning, longing and blitheness of the original, especially so when he underlines the latter emotion with a crescendoed play. This is one of the rare inclusions where I can definitely state that both the vibraphone and the piano are equally important and splendid, as both have different mood-setting tasks: Rains plays the vibraphone in a jumpy, unvarnished way that is at first a counterpoint to the piano section. But both together create an entrancing concoction and make this one of the most celebratory songs of mystique.

Shangri La by Dune Kailua is a special song due to its inclusion of a thin shawm-like organ which accompanies the laid-back six-note piano chord theme. The aura is sunset-red, and the prominent maracas merge well with the dreamy atmosphere which is further nurtured by Rains’ complemental vibraphone gleams. The organ is a curious choice, as it was never used before by the band … and never since, for we reach the closure of the album; the band takes a bow before the third-stream movement with its eclectic and dynamic tone sequences. Jasmine And Jade by Axel Stordahl and Henry Beau is a clear-cut brass song and cannot be linked to this kind of music at all; originally the brassy title track of Stordahl's 1960 album Jasmine & Jade, his second Exotica offering overall, the metamorphosis thanks to Gene Rains is all the more stunning. Convoluted patterns of cymbals, ever-changing vibraphone-piano couplets and rhythmic shifts make this an electrifying track that is perfectly suitable for the complex compositions that Rains featured on his debut Lotus Land. However, Jasmine And Jade is no experimental track, at least not in the hands of the Gene Rains Group, for it is perfectly embedded and padded in a rose-tinted luminescence of cozy and exotic tones. It’s quite a bit more exotic than Stordahl’s original, but the group retains just enough of its mercurial attributes (sans its brass sections, of course) to make it shimmer through this whitewashed retake. And so ends the group’s best and last album.

Rains In The Tropics is without a doubt one of the best vintage Exotica albums and the culmination point of the band’s skills. Whatever lead to the group’s sudden demise – only the Best Of collection Call Of The Tropics was thrown halfheartedly at the craving fans as a fourth release – and their disappearance, no reason can be satisfying enough to justify a fade-out into the distance. It is clear that 1962 showed the first signs of a slowly growing fatigue of the Exotica phenomenon, true, but neither did the group react to newly arriving trends such as organ-fueled pre-Funk music or the rise of Rock music in general, nor did they start solo careers or other band-related projects where the members could really shine. I can continue crying about this, bathing in nostalgia and compassion due to Exotica’s sunset phase, or I can worship the Gene Rains Group with a deep passion. Naturally, I tend to do the latter.

With the exception of the opener of side B, Shadow Of Love, which doesn’t cater to my taste, the remaining eleven tracks are highly melodious and very good overall, with five gargantuan gobstoppers whose beauty and multiple layers can be unveiled in a similar fashion to the sugary jawbreakers. Tiki, Mapuana, Soshu Night Serenade, Lonely Winter and Flamingo are altogether terrific renditions, and it is no coincidence that the majority of them belong either to the dreamy or the mysterious kind of Exotica … or to both! The Far Eastern flavor that is interspersed through many tracks is always welcome, but it is the strict focus of the group that makes Rains In The Tropics such a lush recording: they get rid of any unnecessary elements and don’t broaden their pool of instruments for the sake of it. No birdcalls are featured, and only the koto and that thin organ provide an unexpected expansion of the band’s instruments.

It is crystal clear that Exotica fans need to own all of the group’s albums, but seriously, if I had to choose but one single album, I would go for Rains In The Tropics. It would be a somewhat sour choice, for in the end, I had to neglect the wonderfully dreamy Far Across The Sea, but luckily, that’s just a thought experiment anyway. All instrumentalists involved were really at their creative and skill-related peak with this album, and they (had to) quit when it couldn’t get any better. Over 50 years later, this album is still unavailable on digital music stores or on CD’s, but I feel that somewhere, some important person will green-light a release sooner or later. And when that time comes, the people who are raving about Gene Rains will increase and rightly hail him as the third important man of the Exotica genre. Recommended to the max!

Ambient Review 102: Gene Rains – Rains In The Tropics (1962). Originally published on Aug. 4, 2012 at AmbientExotica.com.