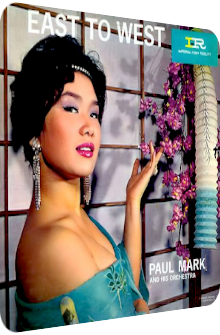

Paul Mark

East To West

1961

There is no Exotica album like Paul Mark's East To West, regardless of whether one takes the organist's own 12½ Geishas Must Be Right (1963) or Tak Shindo's Far East Goes Western (1962) into account, thinks of the Tokyo Serenaders' Holiday In Japan (1950's) or adds Werner Müller's eponymous album from 1958 to the agenda, no other act or orchestra can unchain the same multiplicity of Lounge, Space-Age, Exotica and Far Eastern traces. Not much is known about the US-American arranger with Asian roots, the birthdate and curriculum vitae are veiled in myth, but rest assured that Paul Mark knows how to handle a piano and especially the Hammond organ very well. East To West is recorded in 1961 at the Oasis Nightclub in Honolulu, released in the same year on Imperial Records and has thankfully been re-released several times from 2011 onwards in the shapes of digital issues.

Paul Mark's orchestra is actually a septet on this album, with Paul Mark on the organ and piano in one single instance, Tomo Fukui on the guitar, Benny Lagrimas as the percussionist, Samisen Toyosumi (undoubtedly an alias or nickname) on the Japanese banjo called shamisen, Kay Mikami on the koto, Joe Mullan on the double bass and the bongos as well as singer Midori Kawaji who is featured on two compositions. Speaking of compositions: a whopping 14 tracks made it on the album, and since two of them are medleys, the total amount of tunes grows to a jaw-dropping 24; supreme variety! Most of them are either traditional children's songs of the East and the West, with the other much stronger leitmotif being songs about love and departure, hope and dreams, present and future.

The incessant mixture of Paul Mark's Hammond organ and celeste with the gongs, xylophone, koto and shamisen is awe-inspiring and unique in the Exotica landscape. Some tunes are Rock-like and joyful thanks to the simulation of a fairground organ, others bathe in mystique and darker half-tones. Exotica fans who are fond of the Japanese tonality will be happy to know that East To West features two to three tunes that reappear a bit more regularly in their favorite genre. The rest is excitingly alien and deliciously strange, so without much ado, here is an in-depth look at an highly intriguing artifact of Japanese Exotica.

The album launches in a downright mystical fashion full of glitzy glockenspiel sparks and clichéd yet oh so wonderful Japanese piano spirals in higher regions: Hietsuki Bushi is a splendid opener, a traditional Folk dance which Paul Mark transforms into xylophone- and bamboo rod-laden percussion lands. Mark's sizzling hot organ is a top-notch addition in adjacency to Kay Mikami's koto, the composition is loaded with jots and blebs, Chinese gongs and an uplifting atmosphere. Tomo Fukui's guitar accents function as stabilizing, warmhearted columns in an otherwise effervescent tittlescape. Kokoni Sachiare is next, which the liner notes cryptically link to either the movie Love Is A Many-Splendored Thing from 1955, starring superstar and Exotica collector William Holden, or the well-known saying. This tune is less glaringly Japanese, as it favors the colorful organ washes in-between a diffuse Waltz-like rhythm and Fukui's guitar scents and Toyosumi's shamisen shards. But the good mood is upheld notwithstanding.

While the gorgeous ode to Tokyo's picturesque bridge Oedo Mehon Bashi is an oscillating masterpiece ranging from glittering crystals, Joe Mullan's bongo aorta, a dusky alto flute and a shady organ shrapnel next to a rhythm guitar frame, altogether ingredients that are decidedly Polynesian yet inducing the Japanese spirit, the following Children's Medley is a rather dubious tune, pointing to the album title in all of its glory: nine perfectly Occidental children's songs are performed with kotos, shamisens and other Japanese instrumentals plus Mark's Hammond organ, among them Jack & Jill, Oh Susanna, Why Don't You Cry For Me, Yankee Doodle, Old McDonald and This Old Man. The rapidly cross-fading change of each chorus and the carnivalesque setting remind of Arthur Lyman's tendency in the 50's to present a cheeky or military march-based tune as the outro. Children's Medley provides a comic relief, but is otherwise de trop due to its gimmicky structure.

Lyman fans know the next song by heart from his exotic debut Taboo (1958), Martin Denny's Exotica Volume III (1959) or Gene Rains' Lotus Land (1960): Ringo O Iwake is a gorgeous koto-infused take on the traditional Folk song about a young woman gazing at an apple orchard as she is remembering her lost love. The brightness of the glockenspiels works well in tandem with the crepuscular organ scheme and the cavernous gongs, only in the second half does Paul Mark's interpretation brighten up before the delicately outlandish staccato koto twangs fly over the listener. A fantastic take! Akai Rampu No Shu Resha then takes place at a train station, as it is about a girl who waves her loved one goodbye. The field recording of a train seamlessly floats into the music. It features an almost Yiddish rhythm, the koto bounces through the organ-wadded thicket, warbled flutes resemble the signals and the glockenspiels point to the ensuing loneliness in an otherwise bubbling take. Side A finishes with Itsuki Komori Uta, a bamboo rod- and bongo-interspersed blazingly Japanese song, actually a lullaby of Kyushu. It is rather shady and full of twilight, still catchy but not in the slightest way resemblant of US-based lullabies.

Side A bursts at the seams in regard to its unique blendings – even when one considers the Exotica genre's flamboyancy –, and side B does not disappoint either, for it features Japanese melodies that dedicated experts of the genre know well. Chakkiari Bushi, the opener of side B, is probably not among them, but its cheeky upbeat physiognomy is nonetheless enchanting. A song that is traditionally played during the tea harvest, it meshes the air (iridescent glockenspiels and coruscating flutes) with the woods (claves and xylophones) and rounds things off with fire (koto riffs and hot organ bridges). The popular Japanese Waltz Hana Kota Ba No Uta then hits a new nerve, for it is a dreamy piece of Ambient Exotica, a first on the album. Instead of chopped tone sequences, everything floats in legato runlets. Faithful crystalline lullaby structures function as the prelude and lead to a mellifluous mirage of Space-Age organs, sweeping shakers and blurry hi-hats. Short injections of Tomo Fukui's guitar and Samisen Toyosumi's, well, shamisen round off the sound in unison with Joe Mullan's double bass accompaniment.

The following Andu Ban Dai Zan is a bustling ever-changing critter of a tune. Being a traditional tea house song, one feels the aura of the busy location, the clash of a flurry of activity with tranquility. The opening section is already anything but super-gorgeous: Mullan's bongo solo is elevated by resplendently aqueous-synthetic organ vesicles that resemble today's video game-based jingle culture when choosing items while being in the options menu of a Japanese game of your choice. Jazzy double bass spirals, triangles plus cymbals, a rhythm shift and many alcoves through which the bongos shimmer, make this a a tune that is perfectly compatible to Western ears, almost Latin in its percussion, then again Bachelor Pad-oriented and rooted in the Space-Age era. As I've said: a bustling ever-changing critter. And mind-blowing.

Another children's song is next, a Japanese one this time. To Ryan Se depicts the – now well-known – dichotomy of fairy tale-like luminescent mallet instruments and opaquer double bass motifs. Never entirely heartwarming nor embracing, To Ryan Se lightens up a bit once the elastic plasticity of the koto is added. Midori Kawaji murmurs in the background, wooden percussion instruments serve as the backdrop. A great tune! If all Occidental children's songs were like this, this culture would benefit. Up next is Hana Gasa Dochi, a Japanese #1 hit from 1908 about a girl praying to buddha that she may marry the boy she loves. It is strongly gleeful and jocular with organ stabs in major, glockenspiel droplets and mellow hi-hats in-between the typical ebb and flow of a Jazz rhythm. Bongo flecks and acoustic guitar globs of enchantment round off the most saccharine but never cheesy tune of the album.

Wakare No Isochidori is yet another song about love, departure and parting embedded in a jazzy rhythm with spectral organ airflows, Fukui's guitar licks and an entanglement of the koto with the glockenspiel, all of them rounded off by Midori Kawaji's lyricless chants. This is sadly the only time she is in the spotlight, for the final Sakura Fantasy Medley is near, a magnificent three-part koto-fueled medley about springtime. The field recording of a nearby lush stream, the susurrant organs and Kay Mikami's skills on the koto erect another hugely exotic superimposition, with the middle part of the medley comprising of the nocturnal mystique of Sakura – an often-interpreted piece in Exotica lands, ranging from versions of Martin Denny over Arthur Lyman to Werner Müller – and the final piece being akin to a pandemonium with its heavy organ protuberances and wooden percussion splinters. With a final three-tone staccato on the organ, East To West ends with the expectedly pompous bang.

East To West is an enormously powerful album. It is somehow rooted in the realms of Easy Listening, with Paul Mark being perfectly aware of the picayune allusions that come with the genre, and yet there is a duality of cheekiness and seriousness, joy and threnody, lachrymosity and humor. With the exception of the failed experiment in delivering a Japanized take on Western children's songs, all remaining 13 tracks glow and glitter due to Far Eastern tonalities, timbres, textures and traces. The ubiquity of the organ is probably the most stringent or coherent feature, but right after this particularity, the koto, shamisen, glockenspiels, gongs and bongos wait in the queue, ready to be dropped in each song.

I have my strong favorites, as I tend to with every album, but East To West offers a cohesion that makes it hard to objectify a subjective perception. I am not being lazy here, it depends on the listener's favorite sound color and mood, and moods there are aplenty anyway. Paul Mark does not poeticize or exoticize the aura of Japan, he tries to merge the fragility and alienating tonality with Western concepts and a bunch of bongos, so to speak. In contrast to the Exotica genre in general and some of the works I mention in the opening sentence of this review in particular, East To West neglects an all too huge variety – Werner Müller comes to mind who sits on the opposite spectrum – and draws from the same instruments and mixture throughout its runtime.

There are minor flaws though: the beautiful voice of Midori Kawaji is only boldly featured on one track, with her being strictly in the background on a second one. In addition, I would not have minded an even stronger inclusion of the bongos, as unfitting this may seem; a short solo here and there would have improved the Exotica flavor… while admittedly diminishing the truthful Japanese scents. Regardless of how you approach this album, it is one of the very finest Japanese Exotica albums of all times, almost forgotten or never known in the first place, but thankfully reissued several times recently, often with the original front artwork and song order intact, while other download versions feature stock photos. Even the sound quality varies, so if you want to grab it at Amazon MP3 or iTunes, be sure to pre-listen in order to get the best one which, given this review's publishing date, is the 2013 edition by Marmot Music. I do not think that the master tapes were digitized, but the quality is still great, i.e. without the least bit of hiss or vinyl crackles, with only some diffusion due to the live setting of the Oasis Nightclub in Honolulu. You owe it to yourself to check this gem out if you were not aware of it previously. It is a splendid – or better still: outshining – addendum to like-minded Exotica entries.

Exotica Review 205: Paul Mark – East To West (1961). Originally published on Apr. 20, 2013 at AmbientExotica.com.