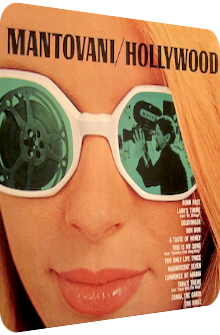

Mantovani

Hollywood

1967

Hollywood by Anglo-Italian conductor and arranger Annunzio Paolo Mantovani (1905–1980) is a twelve-track journey through various decades of Oscar-winning movies and their themes. Released on Decca Records in 1967, I could leave the review at that, as the concept is completely transparent and not particularly exotic, for the themes from Tarzan, Geisha Boy or The Bridge On The River Kwai are completely amiss. And yet, there is much to write. Hollywood and Exotica go hand in hand. Not only was the first-ever properly named Exotica album recorded in Hollywood in December 1956 and released straight in January 1957 – Martin Denny’s Exotica –, the scope, arrangement and theme of many a production is in addition as vivid as the famous plastic pipe dreams of the floodlight-illuminated studio sets.

Then there is the constant hit-or-miss cavalcade which pesters Mantovani's album, making the listeners clap their hands in one moment, only to then wade through an arrangement that is so incredibly close to the original that its inclusion for aesthetical reasons can be ruled out entirely. The three basic columns of Hollywood are hence as follows: first Crime Jazz, second Space-Age with Exotica blotches and finally bog-standard realizations of the original compositions without many changes. Vintage movie fans will clearly get the most out of this work, with Space-Age fans having a field day as well. Since there are also little Exotica sparks on, in and around the album, chances are that even these fans might raise a brow of interest or two. Here is a closer look at a fittingly cinematic album.

The opener is one of the most exotic themes of the whole album, at least potentially so, but its appearance seems all too streamlined: Don Black’s and Jon Barry’s Oscar-winning theme to the 1967 movie Born Free underlines the story of a cute lion cub which sooner or later is going to live by itself in the wilderness. Mantovani’s orchestra, in short, cries you a river. The heartwarming – and not to be ridiculed – eight-note motif is realized by shedloads of orchestra strings and accentuated by actually splendid guitar licks, but the whole arrangement does not offer anything new and is sternly attached to Barry’s original sheet music. Even the golden-shimmering horns cannot rescue the blandness. Again: the theme is famous for many reasons, Mantovani’s arrangement, however, is a copycat commissional work.

Up next is Lara’s Theme by Maurice Jarre, a sequence off the 1965 epos Doctor Zhivago, and it is much more successfully transformed here and wonderfully akin to a travelog: the strings are flying into Space-Age territories while retaining the festive overtones of the original. It is the cool slap bass, the savoir vivre accordion and shell-like percussion which make this more of a stroll on a promenade than a theme reserved for the beauty of one particular woman in a large ballroom. The rather thinned state is appreciable overall, for the strings are now much more enchanting when they hit out of the blue.

Mantovani’s time machine travels back farther in time, a few months prior to Doctor Zhivago and straight into 1964, to be more precise, and brings us the histrionic-historic cinematography of the 007 Goldfinger theme, envisioned by John Barry, Anthony Newley and Leslie Bricusse. This rendition is again somewhat flawed, as it is attached to the original incarnation like a leech… luckily, it is a leech on steroids. Although Shirley Bassey is unsurprisingly amiss, the tempo is increased, the admixed tambourines and rhythmic horns deke or cautiously hint at a swinging rhythm, the Chinese gongs add an aura of mystery, with the string-and-horn alloy being towering as usual. 1959 and Miklós Rósza’s Ben Hur are next on the agenda. A pompous yet expected echopraxia of the original version full of – admittedly gorgeously – meandering string movements and tramontane horns of glory, it is Bobby Scott’s and Ric Marlow’s A Taste Of Honey that may be the artifact that is closest to the Exotica genre, if only for the fact that Martin Denny delivered two albums that were inspired by the drama movie and composition from 1961.

Annunzio Paolo Mantovani’s string euphony is only partially spacey. It is factually much more glacial and portentous, dedicatedly serious and a tad too fraught with meaning. This is only a problem within this website’s given context, so side A’s finale, called This Is My Song off A Countess From Hong Kong, sees Charlie Chaplin’s vision come to life here by means of rose-tinted string airflows complete with elysian adjuvants, carefully set accordions as well as quavering bass flutes which work well with the solemn gravity and wideness of the arrangement. Another faux-marker of a travelog album, this is an almost divine interim closure.

Side B oscillates between the same amount of Crime Jazz, big band allocations and Occidental ballads. John Barry and Leslie Bricusse celebrate their encore with 1967’s You Only Live Twice, one of the mildest, almost mellifluous, Bond themes. And indeed, Mantovani’s orchestra pleases the fan of symphonic Exotica with this particular piece. The main melody is realized via glissando-heavy legato string undulations as expected, but it is the Far Eastern marimba droplets that make all the difference, not only linking to the movie setting, but inheriting that spirit of languor and yearning. Leonard Bernstein’s theme from The Magnificent Seven, meanwhile, sees its 1960 appearance ameliorated by gentler staccato horns, polyphonic accordion accents and murky trombone formations. Add the Latin lead trumpet to the scenery, and you get another successful rendition.

While Max Steiner’s Tara's Theme from Gone With The Wind preserves its 1939 technicolor aura unchanged due to the faithful reproduction of its original gestalt and only experiences a rhythm guitar-accompanied upbeat change in the second part which is further affected by Balearic guitar schmaltz, Maurice Jarre appears a third time on this album with his gargantuan theme of Lawrence Of Arabia (1962). No surprise here, Mantovani’s interpretation is closely attached to Jarre’s vision, but the middle section is super-exotic thanks to the droning timpani, the Oriental brass tones and plinking tambourines. Comprising four different sections with quiescent passages and muggy vestibules to foreign deserts, it is, in the end, a great take. Mikis Theodorakis’ Waltz structure of Zorba, The Greek off 1964’s Alexis Zorbas is then tastefully altered via ligneous xylophone blebs, flute fusillades and accordion warmth, with the virtual apotheosis The Bible, written by Toshiro Mayuzumi for the eponymous 1967 movie, being a simple repetition of the original, making me wonder why genius and copyism are so closely tied to each other on this album.

Mantovani’s Hollywood is not as glitzy and coruscating as the most wonderful of all places on Earth – I’m exaggerating here for the sake of gullible Space-Age technocracy – but it is a fitting title after all, if only for the fact that all compositions are based on famous and/or Oscar-winning movies. Alas, there is mot much else to the formula the Italian conductor and arranger chose for this particular work. It is striking (and close to being abhorrent) how closely attached the artist remains to the source material, even on purpose. I can fully understand that the original composers and movie studios do not want to see their world-famous compositions ridiculed, mocked or changed to become diametrically opposite mutants or Merengue ditties, and granted, many of the 60’s movies were as young as three years at the release date of Hollywood. However, this should not prevent a skilled man like Mantovani to come up with different instrumentations. This wish is all the more striking as it is fulfilled over the course of this album! T

he renditions of Zorba the Greek, Magnificent Seven and Lara’s Theme prove that clever accentuations can change the perception of the composition in a positive way, even though the lead melody remains unharmed. Whatever the reason for the faithful reproductions is, there are moments where even this aforementioned copycat procedure causes surprises: the infamous Goldfinger theme is sped up in order to become more vivid and literally moving than before (one might hope), and let me not forget the four-party amalgamation in Lawrence Of Arabia which makes this a little suite of different patterns not unlike Dominic Frontiere’s micro suite Festival off his Exotica milestone Pagan Festival (1959). To be honest: the typical Exotica listener (who’s that, by the way?) does not need to check out Mantovani’s Hollywood, but film buffs, Space-Age aficionados and Crime Jazz luminaries may dig many of the arrangements. And then there is always the reason of contrastive analysis: what little particles did Mantovani hide amid the seemingly standardized deliveries? Hollywood is all yours on vinyl and a remastered digital reissue on iTunes, Amazon MP3 and their streaming service foes.

Exotica Review 356: Mantovani – Hollywood (1967). Originally published on Jul. 5, 2014 at AmbientExotica.com.