Yma Sumac

Fuego Del Ande

1959

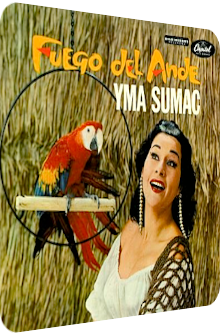

Fuego Del Ande is the sixth studio album of Yma Sumac (1922–2008), the octave-climbing enchantress extraordinaire bona fide and her first stereo record as well. Released in 1959 on Capitol Records, it continues the artistic collaboration with her then-husband Moises Vivanco (1918–1998)… but neglects almost everything else that has been key to her success! The front artwork reveals more than usual. First of all, Yma Sumac is indeed smiling graciously in a surprisingly bright and lucid setting which is at the same time minimal. And indeed, this minimalism, coupled with the toned-down suit, provides the base frame of the twelve songs, all of them adamantly folkloristic, with one unique song contributed by Vivanco himself.

Fuego Del Ande unsurprisingly enough promises a fiery affair, an aural anhydride seasoned by calcined guitars, annealed castanets and weirdly twisted piano percolations. In lieu of the scything brass fanfares and their humongous scope on 1954’s Mambo!, Sumac under the supervision of Moises Vivanco flourishes and whirls through a dry mountain range with only the barest scents of Andean mysticism perceptible. This is an affront, true. But it is also an experiment that works out well. During that time, there was the question of how Yma Sumac’s over-the-top glamor could be integrated into established touchstone classics, providing a weird twist to their authoritative aura of community music. Fuego Del Ande gives the answer… embedded in castanets, guitars, sparse drums and a choir that is rightfully put to the foreground in Yma Sumac’s comparatively unadorned Latin escapade.

It’s a trap; a suntrap! Never before has Yma Sumac emanated such a sun-dappled aura: her interpretation of Francisco Ballesteros’ La Molina (The Mill Song) is mercilessly orthochromatic to begin with, be it the mountainous aureate guitar chords, the galloping boo-bam reticulation or the temptress’ own reciprocation between energetic falsettos and octave-crossing high-rise barnstorms. The male choir rounds off the gleeful aura, and does so many times throughout the album.

Chabuda Granda’s Flor De Canela (Cinnamon Flower) even augments the folklore spirit with crimson Flamenco guitars, castanet lariats and oscillations between fiery devotion and laissez-faire pre-Surf Rock (!) flavors, with Heraclio Cuentas’ Gallito Caliente (The Hot Rooster) serving as the jocund flute-accentuated bandwagon crossing a hamlet complete with sugar-sweet duets, honky tonk pianos and uplifting castanet fusillades, all the while La Pampa Y La Puna (The Plains And The Mountains) by Carlos Valderrama and Ricardo Walter Stubbs ventures into archetypal-histrionic Sumac territories grafted onto a twilight Flamenco: shrill jungle fifes, recondite anathemas and clandestine kaleidoscopes timbre-wise make it the hole-and-corner tidbit of side A. Afterwards, Moises Vivanco’s own Dale Que Dale (The Workers Song) injects guitar-fueled sunbursts and xylophone droplets into the gorgeous – and only – bongo/conga stampede before the traditonal Llora Corazón (Crying Heart) rounds off the eclectic side with a laid-back desiccate bonfire in 3/4 time and a wideness that is literally reflected by the reverberated castanet afterglow.

Side B mirrors the aesthetics and absorbs the tendencies of side A by starting with another very concrete corona. Awash with light and diffractive, Huachina (Enchanted Lake) by Angel De Valle launches with hillbilly-esque guitar zoetropes, flamboyant polyphonies within and around Sumac’s vocals, and a cavalcade of castanets whose omnipresence amid the backing choir make this the strongest folkloristic corker – just wait for the effervescent piano in the last third. Meanwhile, Guillermo Riofrio Morales’ La Perla De Chira (The Pearl) is a superimposition of sunset-colored gypsy tonalities, Haitian syrinxes and Jazz cellar pianos. This explosive mixture tumbles into many a stylish interstice, eventually capturing the quasi-titular ardor of the Andes as its guiding placenta, with the traditional Mi Palomita (My Pigeon) providing an exciting standout mixture of Ragtime riffs, amethystine plucks and an energetic Yma Sumac whose vocals provide phylogenetic hints of her success more often than not.

Jorge Bravo De Rueda’s Virgenes Del Sol (Virgins Of The Sun) follows, morphing from a cinematic-ecstatic fanfare over Gothic vocal convulsions to euphonious Surf attitudes. The thiazidic Doppler elastics of the mixed choir have to be heard to be believed in this catchy critter! Subsequently, Edmundo Zalvidar’s Gallito Ciego (One-Eyed Rooster) showcases similarly memorable – and majestic – staccato pianos as a gleeful current washing over the good-natured sorceress and her choir. It is the finale in the shape of Elisiario Rueda Pinto’s Clamor (I Won’t Forget You) that returns to the tawny, polysemous kind of tradition where the gravity of the castanets, chords and vocals is both pompous and portentous… and make this the last visit of the convoluted driving factors of this here album.

Fuego Del Ande is the occasional yang to Yma Sumac’s yin, providing a more festive, earthbound, realistic counterpart to the legendary singer’s riddled orchestrations, enchanted coppices and spellbound allure. In lieu of vivacious strings and lavabo horns, Vivanco & Sumac return to the most traditional Latin songs played in the Andes and elsewhere. This project is therefore the infamous case of a hit-or-miss-affair, now dangerously annihilating the expectations of both fan groups: neither is it as polyfoil and amniotic as the siren’s Legend Of The Sun Virgin (1952), nor as aggressive a plasticizer as her aforementioned smasher Mambo!, what with all its accosting (or was that cajoling?) high-energy drum profusions, horn cataracts and cryptic outbursts… disguised as an accessible Latin spirit. No, Fuego Del Ande is turned down a decisive notch, even more so than its predecessor Legend Of The Jivaro (1957).

When North America soaks in the Exotica craze, Yma Sumac has already seen it all in the beginning of the 50’s and rightfully moves on, now presenting an album that is anything but jovial folklore with a few cloak-and-dagger discrepancies hailing from the distance, never making the colorful atmosphere their own. While both fan bases of Yma Sumac are alienated and consider Fuego Del Ande less frequently, it is worth mentioning – and listening to of all things – due to the unapologetic earthen realness of the material. The enchantress and her choir are closely entangled within the Latin tendrils and stylistic rhizomes, providing an uplifting record that will ennoble many a bus journey, camel ride or sightseeing tour through Latin countrysides and small towns, even today. It’s an album for daytime… a curious mutant in Yma Sumac’s regimen over the night. Available on vinyl, CD, streaming services and as a download.

Exotica Review 416: Yma Sumac – Fuego Del Ande (1959). Originally published on Feb. 21, 2015 at AmbientExotica.com.