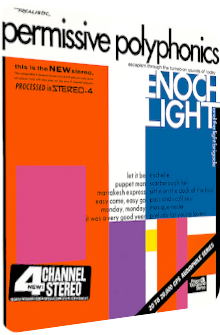

Enoch Light

Permissive Polyphonics

1970

When mankind reached out for the moon, everything was possible in all areas of expressive art. When mankind reached the moon, however, a lot has already been said and done, and every Space-Age record after this achievement is but a mere addendum and supplement to the dreamers. That’s the pessimistic way of analyzing music history, as the rise of synthesizers allows myriads of Funk in a time when big bands are on the decline, but still a big thing after all. Within this timeframe, bandleader and recording engineer Enoch Light (1907–1978) releases two albums that show the discrepancy between excitement and its jejune afterglow: while Spaced Out (1969) is a tastefully outlandish otherworldly capsule that lifts off with the three ever-important B’s on board – Bach, Bacharach, Beatles – and chock-full with uplifting choirs and electronics, 1970’s Permissive Polyphonics faces the aftermath of the landing on the moon… and resides on Earth.

Gone are the days of cosmic glitter, but their atoms are nonetheless sprinkled over 12 swinging and laid-back tunes, two of them originals written by Light himself. Released on the Project 3 Total Sound label, Light admixes Dick Hyman’s organ and harpsichord prowess and lets it conflate with Dick Lieb’s Moog synthesizer before a 17-piece-ensemble of skilled musicians. The drum section is pretty lackluster and doesn’t feature anything out of the ordinary, but the established euphony of the various brass layers, woodwinds and guitars works well. Shuttling between excitement and withdrawal, Permissive Polyphonics is for listeners who have experienced a multitude of Space-Age albums prior to 1970 and are keen on a cozier afterthought. That’s it in a nutshell, all other quirks, compunctions and successes are analyzed below.

Enoch Light’s version of Graham Nash’s Marrakesh Express leaves the train station just in time and allows a comfortable journey throughout its runtime of three minutes. Julie Ruggiero’s swinging bassline is soon alloyed by Vinnie Bell’s electric sitar. These wonderfully apocryphal devices – it is the 70’s after all – are rounded off by saxophones and a mixed choir succumbing to the quirkiest of all romantic lyrics, “I smell the garden in your hair.” Moving right along: John Lennon & Paul McCartney’s Let It Be’s only two surprises are a fuzzy piano played in Honky Tonk style by Derek Smith and Dick Lieb’s sawtooth Moog synth which scythes through the lachrymose-efflorescent choir of aging hipsters, while Christine McVie’s and Eddy Quintela’s Easy Come, Easy Go works much better due to its blurry mélange of marimba droplets, various alto woodwinds and pointillistic gouache droplets. The whole song feels like daubing watercolors indeed, cautiously spacy, always earthbound.

Howard Greenfield’s and Neil Sedaka’s Puppet Man then ups the ante via Dick Hyman’s molten lava punctilio as unleashed by his Hammond organ which has to elbow away Dick Lieb’s crazily oscillating Moog starlight amidst the ba ba ba Space-Age vox, before Enoch Light’s own Prelude For Young Lovers provides an enchanted cavern with plinking legato flutes, stacked downwards-spiraling chord progressions, oneiric guitar layers and doo-dooing ascriptions by the choir. The finale of side A rolls along in the shape of Ervin Drake’s It Was A Very Good Year. Its melancholia is presented here with moisturized brass sinews which carefully protrude the fragilely alkaloidal haze of organs, flutes and some nastily wobbling Moog. Two contrapuntal forces entrapped in a cave, glittering chimes and rustic Moog stabs, provide a bewildering epicenter.

Enoch Light and his fellows continue to be permissive on side B: whether it’s Jorge Ben’s world-famous Mas Que Nada appearing in a splendidly susurrant vibraphone-accentuated midday mirage of simmering harmonies and cosmic synth droplets, John Phillips’ Monday, Monday schlepping itself forward in order to maintain a semi-mournful hammock helix of amethystine Moog mergers and Gospel-like choirs as well as guitar-underlined brass cappers, or Steve Cropper’s and Otis Redding’s appendix Sittin’ On The Dock Of The Bayabsorbing the Sunday-esque Monday Blues by pouring it into a blazing brass fest, Permissive Polyphonics offers what its name promises.

The last quarter of the album is a hit-or-miss affair, as is always the case when famous stompers are interpreted by anyone else but the original creators. Since the release of Enoch Light’s LP, their impetus has grown tremendously, but this is to no avail when the listener encounters these classics in the form they are presented here: Simon & Garfunkel’s Scarborough Fair is transmogrified into a Space-Age peritoneum of – truly mesmerizing – cylonic Moog-driven bouncing balls of discordance, a bouquet of two flügelhorns, acidic but tame electric guitars and mephitic turbulences in the aural air. I for one find this version fascinating due to the simultaneity of mayhem and languor, but if your mileage varies, you have better reasons than I! Lennon & McCartney’s Michelle meanwhile dresses as a dreamy wonderwall whose mysterious-melancholic aura is successfully maintained via caproic woodwinds and the least amount of synth-related gimcrack. Enoch Light’s own Pass, And I Call You rounds off the album with a Space-Age tunnel vision of aureate brass stomps, vertiginous organ molecules and echoey-polyfoil Moog elastics. A genuinely great end- and highpoint.

Enoch Light’s albums are generally dismissed by the music-loving audience for all the right reasons. While they showcase a tendency of concentrating overly much on audiophile recording techniques, the results are good craftsmanship from an aesthetic viewpoint, although they are not exciting enough to warrant a closer inspection decades later… or for decades to come. Permissive Polyphonics resides in this spectrum of repellent ignorance, but has indeed an important trump or two that can be cherished in all honesty. First, the spacy-spatial quilting of Moogs and synth patches is a delightful addition to both the vibrantly swinging pieces and drowsy pipe dreams that are put to the table.

In their best moments, the organs and synths create suitable contretemps and bellicose serrations that work flawlessly in the euphonious riverbeds. Even at higher volume levels, this foreign matter is somehow compatible to the sceneries against all odds. In addition, the source material is wisely chosen, offering a mixture of tangible immediacy and hazy permutations of evergreens. That these things are not everyone’s cup of tea remains crystal clear. What I want to focus on instead is the righteousness of this LP to carry the title Permissive Polyphonics, for the stacked Moog layers and aggrandized guitar or brass strata are indeed permissive and admissive, making this post-Moon Race artifact a surprisingly well-groomed and seemingly natural trip that’s easily digestible without risking an overly vapid blend. Available on vinyl only.

Exotica Review 439: Enoch Light – Permissive Polyphonics (1970). Originally published on Jun. 27, 2015 at AmbientExotica.com.