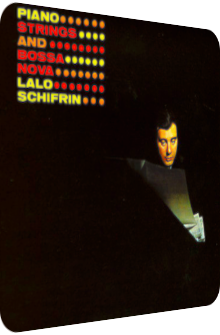

Lalo Schifrin

Piano, Strings

And Bossa Nova

1963

Piano, Strings And Bossa Nova is the – admittedly formulaic yet utterly precise – title of pianist and film composer Lalo Schifrin’s (born 1932) second genre album right after 1962’s Bossa Nova whose subtitle New Brazilian Jazz promised much and delivered even more: an adamantly f-f-faaaast catapult. Flashes of rain forests, paradisiac landscapes and Brazilian bodegas flashed by, making Bossa Nova one hell of a smoking fast affair and a true Exotica album. And then there is Piano, Strings And Bossa Nova, recorded in New York on two consecutive days in October 1962 with a sextet and released in 1963 on MGM Records.

Graced by a crucial string orchestra, the 12 tracks of Brazilian origin – three of them composed by Schifrin for this album – are once again brethren of the Bossa Nova style. This time, however, the speed is decelerated, not just because of the album’s aural endemics, but the expectation by both the contemporary listener and today’s audience. Another Bossa Nova album right after the previous one? This cannot be the best possible strategy marketing-wise, but Lalo Schifrin prevents being trapped and reduced to a specific success-granting formula by making use of said string orchestra.

It is the same trick Martin Denny used on his album Hypnotique (1958) after having delivered seven Exotica albums. Suddenly, the quartet was accompanied by an orchestra and a choir! Was this the first sign that Denny and his men didn’t know what else they could offer all by themselves? I leave this open to debate. Schifrin, meanwhile, leads a sextet to begin with: bassist Chris White, drummer Rudy Collins and guitarist Jim Hall are all astonishingly sparsely audible over the course of the album; percussionists Carmen Costa and José Paulo shine all the more, and this is also true for Schifrin. How does this album cope in the wake of the previous Bossa Nova?

In hindsight, it is so easy to spot particularities in music that became the trademark of an artist or even a whole generation. I do not want to exaggerate the impetus of Lalo Schifrin’s own The Wave which mercilessly rolls over the listener and thus makes for a fascinating opening spot, but The Wave’s spy theme undercurrent is very notable and a marker of the things to come in regard to Schifrin’s movie-related career. Indeed, the slick-portentous murkiness of the motif is as staggering as it is delightful, especially so when it is placed in José Paulo’s maraca forests and harp-infested string billows. The Wave literally shifts into a Bop/Easy Listening dichotomy but remains very accessible and veiled in excitement.

Insensatez by Antonio Carlos Jobim and Vinicius de Moraes provides an interim pipe dream with an upfront coruscation piano-wise, a hazy string moiré in the background and wondrously laid-back maracas. Slight oscillations into more melancholic timbres make the otherwise lofty performance heavier than necessary. You And Me meanwhile returns to the hyperspeed levels of Schifrin’s previous album Bossa Nova as he interprets Carlos Lyra’s and Vinicius de Moraes’ Bossa Nova in a 100 seconds long version full of sparkling vibraphones, Space-Age strings, sweeping shakers and golden-shimmering piano threads, with Lalo’s Bossa Nova showcasing the bandleader’s songwriting skills once again via a swinging conga-maraca potpourri, auroral string bursts and a cannelure of heavily plinking piano prongs. The wafting strings hold the blotchiness together and augment the euphony.

Schifrin does it again afterwards: his creation Silvia is an enchanting wonderwall in the shape of a lead violin which interacts, meshes and melts with saltatory piano accentuations in front of a rose-tinted string cavern. Side A is then rounded off by Djalma Ferreira’s and Luiz Antônio’s Murmurio aka Murmur, an uplifting safari through conga copses, maraca mangroves and piano pinewoods. Dissonant pizzicato strings and the fast tempo mock the song title and create a sophisticated tunnel vision.

Side B opens with Leonard Bernstein’s and Stephen Sondheim’s Maria, a song taken off the 1956 musical West Side Story. It is, in a nutshell, a Third Stream Space-Age extravaganza. Okay, that’s a very large nutshell, but this description basically addresses the gyration between the exquisitely warped strings and their occasional atonality which make the quandary that is Maria all the more valuable. The chromaticity remains glaringly ablaze, making this rendition a bewitching affair… the piano convulsion and bone-crushing drum bombs notwithstanding. Up next is Rapaz De Bem by Aldredo José da Silva, an utter delight due to its eight-note harp aorta, superbly warmhearted-mucoid piano mountain range and otherworldly string washes. Were it not for the frizzling maracas, this tune would have turned out to be a ballad. Instead, it became a swinging piece of dreaminess.

While Djalma Ferreira’s and Ivone Rebelo’s rustic Parrot Samba unleashes its uncoordinated plumage via a reticulation of piano catenae, callisthenic tone sequences and a stop-and-go motion of string sequences, piano solos and Tartarean tandem turmoils, Schifrin’s own Rio After Dark is less majestically glorifying as its title suggests, for the Argentinian pianist embraces the Bossa Nova rhythms and makes the string reverie an inferior element, going so far as to add cautious strings of horror to the designedly dubious locale, again foreshadowing the cinematic thrill and constant state of veneered agony. How magenta-colored and self-explanatory Leonard Feather’s Time For Love is in contrast! Sweetly sweeping, fizzling along and basking in string cavalcades and aqueous piano lights, this is the Easy Listening-oriented Bossa Nova for vintage fans to enjoy. Harry Woods and Mort Dixon provide the sheet music for the finale: I’m Looking Over A Four Leaf Clover is the quirkily titled fanfaronade and a letdown in the greater scheme of things, as the elaborate piano formations do not fit with the pizzicato confectionery in the first part and only tend to absorb the candy Candela later on.

Piano, Strings And Bossa Nova is another fine work of a pianist whose prestidigitation is as fully developed as his compositional skills. It can be doubted indeed whether a second Bossa Nova album is needed right after Schifrin’s original Bossa Nova from 1962, but a look at the title reveals the sequence and importance of events and is an enlightening endeavor: the piano is unsurprisingly the most important part, the strings are newly added and were not featured on a Schifrin production heretofore, with the Bossa Nova style itself forming only the frame for the strings and pianos to shine. The Bossa Nova style was once in the utmost center heretofore, Schifrin and his band revved up the tempo until a fisheye lense effect was created that can only be improved and outdone by Walter Wanderley’s Batucada (1967).

Even though each of Schifrin’s chosen tracks is poured into the Bossa Nova mould, the percussion and drum sections are rarely ever on the forefront. No eclectic drum patterns, no maraca solos, not even a tropical percussion section graces the album. What Piano, Strings And Bossa Nova lacks in these fields, it magnanimously offers via the interactions between the piano and the strings. Be it the harps, violins or cellos, this is a dream come true for string lovers. Even though the title boldly states this, one would not necessarily expect it. But it is true: this album is for string fans what Lalo Schifrin’s fantastic New Fantasy (1964) is for brass aficionados: an album which carves out the luring qualities of the textures, the galactic moments of elation, the sweetly dissonant countermovements… and all of these qualities are held together by a Bossa Nova alloy. Exotica fans who think that Rene Paulo’s piano arrangements are a tad too minimal will find the string flumes on Lalo Schifrin’s LP most welcome and satisfying. Piano, Strings And Bossa Nova is available on LP, CD and digital incarnations thereof.

Exotica Review 484: Lalo Schifrin – Piano, Strings And Bossa Nova (1963). Originally published on Jun. 23, 2017 at AmbientExotica.com.